Interview with David Alan Harvey

Not content with just reaching the giddy heights of Magnum and National Geographic fame, David Alan Harvey won’t quit until the next generation of emerging photographers join him at the top – and even then it is unlikely. Lyndal Irons tracks him down prior to his trip to Sydney in May as a guest of the Head On Photo Festival. This is an excerpt from a longer article in the latest issue of Capture.

It’s 4am in North Carolina when my online hunt for David Alan Harvey begins in earnest. He is a notoriously difficult man to catch, even with an interview appointment. To reach him I must penetrate the gauntlet of others competing for his attention: curators, editors, friends and the countless young photographers he advises via workshops, Skype, Facebook and his immensely active blog, Burn. “Just let me get a cup of coffee,” he finally asks at 6am, before I am video linked to his fisherman’s cottage on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, USA.

Harvey is a busy guy: a working photographer of the highest level, a mentor and a curator who is generous with his time – when you catch him. After our interview he will write the text for a National Geographic assignment on the area around his beach shack, then he has put aside a month for final work on the shows lined up for Sydney during the Head On Photo Festival in May. This famous generosity and furious work ethic make him both a man of the people and one who is hard to pin down. A man who belongs to everybody.

At 67 he has ticked off the highest accolades a photographer can earn, taken and refused the best jobs a photographer can get and forged a life of enviable creative freedom, though not without hard yards.

Road trips

“Imagine this,” says Harvey, setting the scene of his formative years. “I have graduated from undergrad school, my girlfriend is pregnant, I have a beat up car and I am heading out to continue studying in Missouri, living in a trailer park. There is no Magnum, no National Geographic – just many rainy days, lots of trepidation.”

Nonetheless, initial success came easily to Harvey until, while still in graduate school, his first failure taught him one of his most important professional lessons. At 22 he was granted an attempt at shooting an assignment that might have amounted to a big break – only to have his images rejected by National Geographic. He read the letter from the location he’d spent three weeks of his summer shooting and his heart sank fast: Dear David, You are young and strong. That is good, for what I have to tell you will make you feel sick and old. “For an hour, maybe two, I felt devastated,” said Harvey. “Then I thought, why? I didn’t like those pictures either. I don’t like colour or doing this type of photography at all – photographs I thought were National Geographic in style.”

Harvey realised the magazine had not destroyed his photography, only his attempt at conforming to the expectations of others. It was a mistake he never made again. “From 22 on I never did anything that didn’t have my personal stamp on it in one way or another,” he recalls. “I never worked for anyone else after that. That was my one shot, and I messed it up.” In the future he was determined to protect his creative freedom.

It is easy to do the things you want to do, he claims. The secret is simply to be relentless, diplomatic and to work really, really hard. Even before his responsibilities began as a father, Harvey was ill-content with the hedonistic lifestyle of his surfer friends.

Soon after his first rejection he decided to leave the parties of Virginia Beach and take his camera into the ghettos 15 miles inland to learn about life as others lived. “It was good old-fashioned guilt,” he said. “I was in a white middle-class culture and the only other culture I knew about were black people. So I decided to go live with them and photograph them because I thought they needed help.” Bruce Davidson himself pointed out many years later that Harvey’s resulting book, Tell It Like It Is, pre-dated his own East 100th Street, which covered similar ground-breaking matter, by four years.

With an impressive book under his belt while he was still a student, Harvey had little trouble finding work and was recruited into newspaper photography straight out of college. There, he learned the importance of becoming an expert on other things beyond photography. He studied the crafts of the writers and designers he worked with and did his best to become an expert on every subject he photographed. But he knew newspapers were only stepping stones before hitting the big time.

His self confidence became a self fulfilled prophecy when, in his early 30s, Harvey was invited on to both the staff of National Geographic and the prestigious Magnum collective. Then, the magazine had a readership of eleven million. He rejected Magnum and signed on for an office and a secure salary with National Geographic, but as his pen hit the paper, something felt wrong. Being rejected by the magazine in his early twenties had felt bad for a short time. Being accepted on staff felt somehow worse. “I knew that I had not lived up to my original dream, which was to do something more special than to have a job, no matter how good the job was.”

Harvey remained employed for seven years before leaving both his job and wife for a Leica and new self started projects in South America. “National Geographic was just as angry at me as my wife was,” he recalls. But he remains on good terms with his family and the magazine, who he continued to do assignments for – over 40 in total. When Magnum came knocking again on the strength of his work in Chile and another book, Divided Soul, Harvey was now ready to accept an official invitation by Bruce Davidson and James Nachtwey.

Mentoring

Harvey is critical of pessimists that spout doomsday prophecies for socially concerned photography. While it is true that few photographers can put their children through college on a salary from a single magazine, he said, more opportunities exist for today’s emerging talent than ever before. “A lot of young photographers today say the business has changed; it’s dead. It always seems better before because when you are young you only see the result of the previous generation. You look at yourself at 22 and think there is nothing going on. Of course there isn’t because you and all the others at 21 or 22 haven’t done it yet!”

When Harvey graduated from college, Life magazine – one of the goals he had harboured since he was a 12 – closed. Photography panels back then had the same conversations they are having today, only it was much worse. “For me to get my work out in the world as a young adult, I had to be published in one of two major magazines, so I had to get in the top football team just to play. With the Internet you can be discovered so many ways.”

Read the entire profile in the latest issue of Capture.

Lyndal Irons is a Sydney-based writer and photographer and editor of the official blog of the Head On Photo Festival.

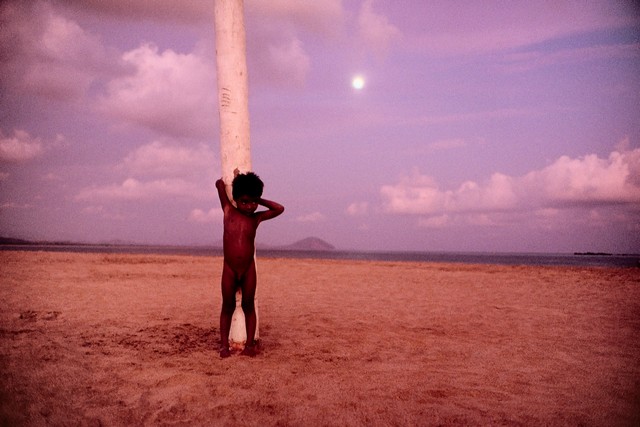

David Alan Harvey’s solo exhibition One Night in Rio will be launched at the Australian Centre for Photography in May as a highlight of the Head On Photo Festival. Harvey will also curate a Head On is also presenting a master class and a Harvey-curated Burn 02 show at Bondi Pavilion, as well as a two-day seminar featuring his input. He will also be presenting at the Semi-Permanent Creative Conference in Sydney in May.